Why are farmers with livestock less vulnerable to climate change?

Fig.1. Photograph by Sabine Homann-Kee Tui

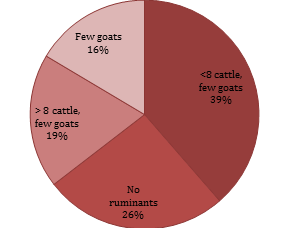

Reducing biomass from rangelands and climate change reduce livestock feed intake and aggravate dry season feed shortages. It hampers farmers ability to sell livestock and buy food when crop harvests fail. Livestock increases production and productivity of the farms. However about a quarter of the households in Nkayi don't own cattle nor goats; they continuously struggle to meet their immediate food requirements, with little cushion against the vagaries of climate variability and change.

For more productive use of livestock it is critical to concurrently improve crop and livestock management and access to markets, rewarding higher offtake and quality products.

Fig. 2. Proportion of households with different ownership of cattle and goats in Nkayi district.

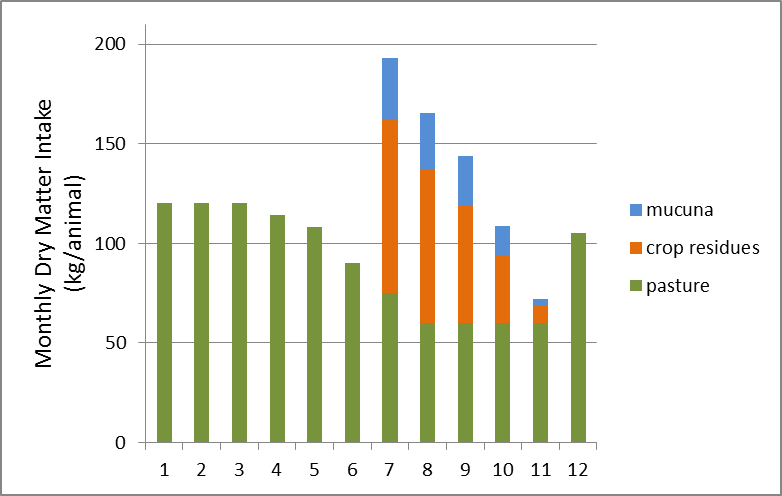

Fig. 3. Feedbase for cattle in Nkayi district, with inclusion of mucuna puriens on one third of the maize land.

What does this information tell us?

Every farmer engages in crop production. However, only about 60% of farm households in Nkayi have between 1 and 25 cattle, primarily for draft and manure, and thus indirectly for food security.

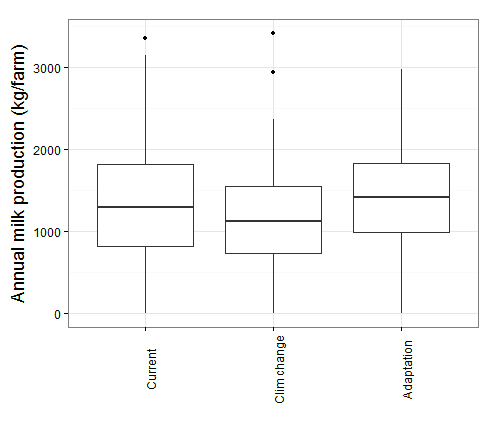

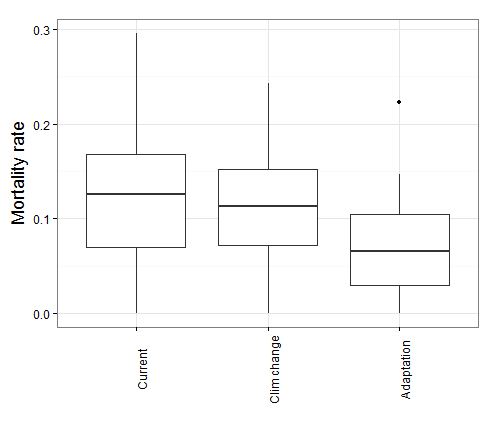

Many farmers complement cattle with goats, another way to diversify and cover against climate risk, as goats are hardy and reproduce fast. Currently only few farmers invest in livestock feed. However, even if climate change extends the dry seasons, supplementary feeding of cereal residues and fodder legumes can address the feed shortages. Feeding is critical for animal health.

Fig. 4. Benefits from feeding livestock as climate change adaptation strategy: Higher annual milk production for family nutrition.

Fig.5 Reduced annual mortality rates: More cattle available for services and sale, at less green house gas emission.

Why is attention to livestock important?

For successful adaptation to climate change, greater attention is needed to the combined effects of improved feed, adequate water supply and animal health. Furthermore, ensuring functional markets is critical, so that farmers realize the full economic value from keeping livestock, motivating them to invest in improved management.

read more >>

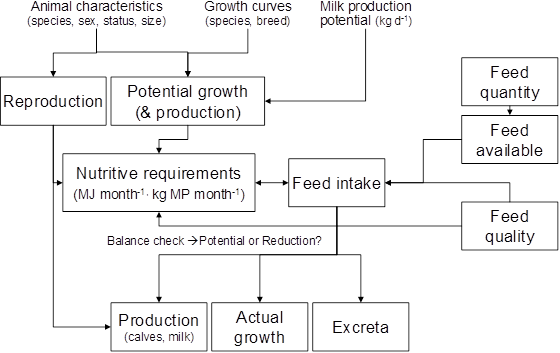

Fig. 6. Livestock model (LIVSIM)

How did we obtain these results?

The effects of climate change were simulated using the LIVSIM livestock simulator, for Mashona cattle breed-specific genetic potential and feed intake. We assessed milk production and herd dynamics such as sales, calving and mortality rates. The predictions were based on simulated changes in on-farm feed supply, increased biomass from crop residues and mucuna pruriens forage, supplementary to rangeland grazing.

The results from livestock modeling were shared and revised at various forums, including local to provincial level farmer and extension representatives, NGOs and researchers.

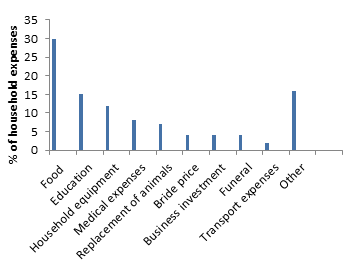

Fig.7. Feed shortages during dry seasons and droughts as most important cause of mortality across the country (adapted from ZimVAC, 2013).

Fig.8. Reasons for selling cattle. Dry season mortalities thus directly affecting food security, education and human health. Source (adapted from ZimVAC, 2013).

Can the results be generalized?

Climate variability and change affect livestock and benefits for farmers in large parts of semi-arid Zimbabwe, where mixed crop livestock farming is the predominant form of livelihoods. Improved management and climate change adaptation strategies must be co-designed by stakeholders within areas of similar agro-ecological conditions and adjusted over time, to also capture other important drivers and market opportunities.