How can climate change adaptation make a difference, for areas where crop production levels are already extremely low?

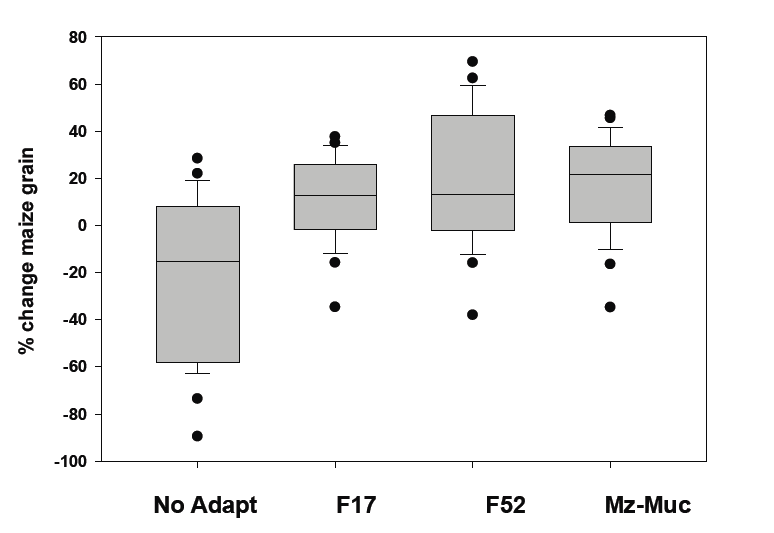

Fig. 1. Maize grain yield increases under alternative soil fertility amendments.

For farmers in Nkayi crop production climate effects alone are not the end of the world: high spatial and temporal variability and harvest outfalls due to drought are endemic. Production levels are so low that losses in production seem not that big in volume. With maize as predominant crop, the value of land is also underutilized.

Diversification and market incentives can encourage farmers to step up from currently extremely low production to substantially higher volumes for food and sale.

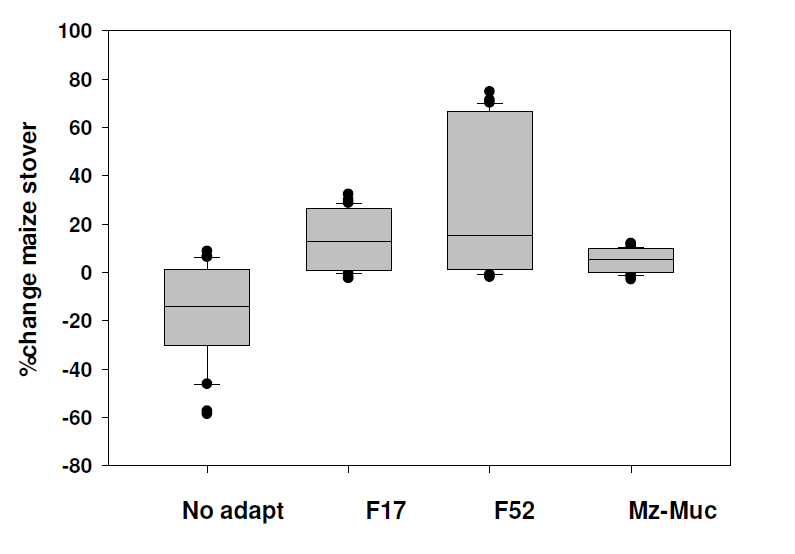

Fig. 2. Stover yield increases under alternative soil fertility amendments.

What does research tell us?

Average maize yields and biomass will decline by less than 5%, in some years by 20%. Yields are notoriously low on the depleted soils. Increased temperatures coupled with reduced rainfall will lead to reductions in grain and biomass. Higher temperatures will favor rapid crop development and shorten the growing period.

Adequate soil fertility is key to raise crop yields: Even though microdosing , and recommended rates would off set yield losses through climate change, clearly maize mucuna, combined with micro dosing is preferable. It shows less yield variation, and hence is the less risky and least costly option.

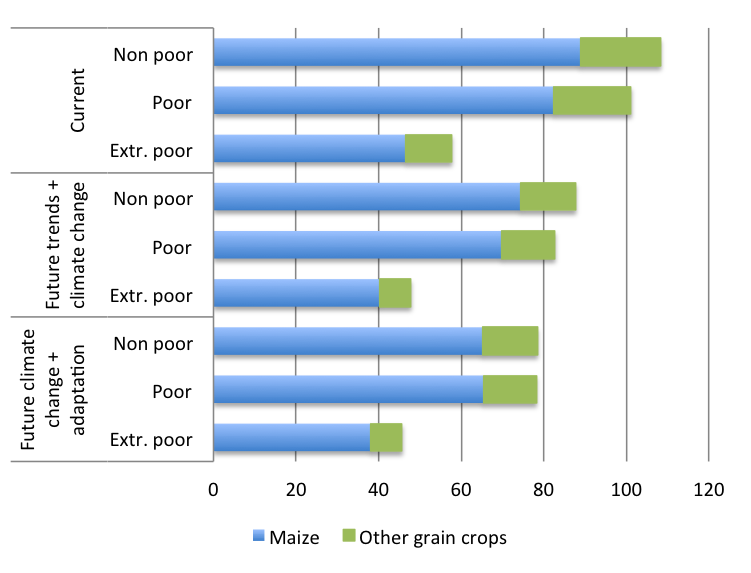

Fig.3 Grain self-sufficiency (% of grain needs per family covered) at risk in Nkayi

Why is this important?

Very low staple production, dominated by maize, means high risk for grain deficits. Small grains and legumes are critical to fill the gap for farmers with cattle. Those without cattle, the extremely poor, are more vulnerable and persistently below food sufficiency.

Climate change and expansion of human population will reduce available land and water resources and threaten grain self-sufficiency for all farmers.

Organic soil fertility amendment would increase the grain gap further. Hence, more drastic measures need to be taken towards sustainable farm sizes and production increases. More land needs to be brought into more profitable use, with higher yields and revenues from crop production.

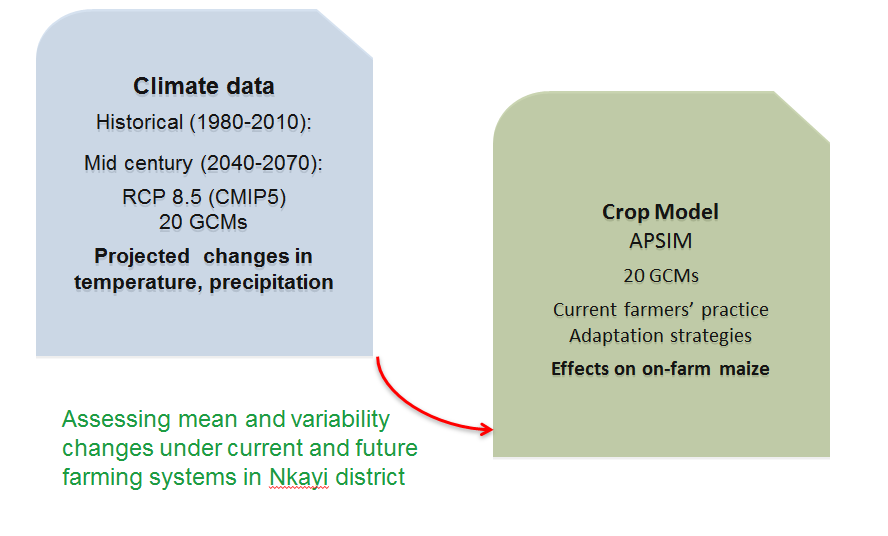

Fig.4 The AgMIP integrated climate and crop modeling approach.

How did we obtain these results?

To assess the sensitivity of the current farming systems to climate change we used the Agricultural Production Systems Simulator (APSIM). We simulated maize production with and without adaptation strategies: 1. micro-dose at 17 kgN/ha on total maize area; 2. recommended rate application of fertilizer at 52 Kg N/ha and 3. a maize-mucuna rotation on one third of the maize land, with 30% of the mucuna biomass left on the fields as organic fertilizer for subsequent maize and 70% fed to cattle or available for sale, and application of micro-dose on one third of the maize field, following the maize mucuna rotation.

read more >>

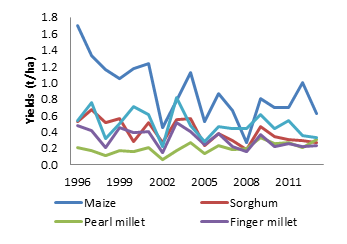

Fig. 5. Yield trends of major food crops in Zimbabwe (Adapted from ZimVAC, 2013).

Can the results be generalized ?

Maize based rainfed agricultural production supports the majority of farms in areas like Nkayi district. The projected 2-3.5 % increase in temperature leading to 5-20 % maize grain and >17 % residue reduction will have a negative effect on the already impoverished smallholder farmers who mostly can only produce 30-70% of food required per year.

Current extension messages recommend diversification into small grain and legume production. Yields of these crops are however persistently low averaging < 500 kg/ha and trends showing decreasing yields.